The post “It was the happiest day of my life, when I took my boy back” – Ivan* and Stoyan’s* story appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>Stoyan* will never forget the night Ivan*, his three-year-old son, was taken from him.

“A policeman came to the door and entered my home without asking and just took him. No warning, no support”, he remembers. “It was terrible.”

Ivan had cerebral palsy, and the authorities decided Stoyan, a single dad on low income, wasn’t fit to care for him. As a result, Ivan spent two years inside an orphanage. Lonely. Afraid. Until people like you brought him safely back to family.

Hope and Homes for Children

The pain of separation

Overnight, Stoyan’s life changed forever. After his wife left, he’d worked night and day to care for their son. But now, everything was ripped away.

“It was horrible”, Stoyan remembers. “I’m a labourer and I was working 12 to 15 hours a day because I couldn’t sleep. My friend told me, ‘If you carry on like this, you’ll kill yourself.’ I was waking up in the night and crying because Ivan wasn’t with me.”

“I was waking up in the night and crying because Ivan wasn’t with me.”

Sadly, Ivan was suffering too.

Inside the orphanage

Ivan spent the next two years heavily medicated. Confined to a cot in a darkened room on the top floor of the orphanage, he’d wait for his dad to visit.

“The institution would allow me to visit only once a week for 15 minutes, between 1030 and 1130 when Ivan was tired and hungry”, Stoyan remembers. And worse, every time he came, he saw his boy’s condition getting worse.

“How was the care? Total zero care,” he recalls. “They tied him into a wheelchair. Before then, Ivan was beginning to stand and walk with support and he had started to speak. He could say mummy and daddy.”

“They tied him to a wheelchair.”

Hope and Homes for Children

For two years, Stoyan fought a lonely battle against red-tape, prejudice and indifference. The odds were stacked against him.

“First, if I take my boy home, the institution loses income”, he explains. “Then, even when I went to court and won full custody of my son, the institution just ignored it.”

Ivan was stuck.

Family first

Ivan’s experience is all too common. Around the world, 80% of the 5.4 million children in orphanages have living parents. And one in three children in orphanages have disabilities.

One in three children in orphanages have disabilities.

European Disability Forum

The one-size-fits-all model of institutional care doesn’t help children. It harms them. Above all, children need love, care and personal attention. Something even the “best” orphanages can’t provide.

Stoyan knew he had to get his boy home. And thanks to your generosity, he found the help he needed.

The fight begins for Stoyan

Since 2011, our team in Bulgaria has been working to close orphanages and bring children living inside back to family. Children like Ivan.

Elitsa Ivanova, one of our support workers, discovered Ivan’s case, and immediately started working to help Stoyan.

“The local child protection department lied to him,” Elitsa remembers. “They kept setting him tasks and challenges but when he met them, each time the authorities let him down again. Because he is a man on his own, people could not see him as the parent for a child with a disability.”

“Because he is a man on his own, people could not see him as the parent for a child with a disability.

Elitsa knew that Stoyan was a loving father. She knew all he needed was some help. And thanks to your support, that’s what he finally received. Help.

Helping Stoyan change the tide

Your donations helped Stoyan convince the authorities he was the best option for Ivan. They helped him find a better place to live, as well as all the essentials he needed to support Ivan and his disabilities.

With your help, and Elitsa’s team by his side, Stoyan brought Ivan back to family.

“It was the happiest day of my life, when I took my boy back,” Stoyan remembers. “Now, we like to do everything together. He is very affectionate, he hugs and kisses me. He likes my stubbly chin so I don’t shave for him!”

Read more about how your donations help parents bring their children back to family.

Hope and Homes for Children

Looking to the future

Today, Ivan’s doing much better. Stoyan says he has seen a rapid improvement since Ivan stopped taking the drugs that were prescribed by the institution. Now, he can stand and walk by himself, and is slowly learning to speak again.

When we asked Stoyan about the challenges he faces, he told us simply, “There are no challenges now. I just love my boy and I am not interested in anything else.”

“There are no challenges now. I just love my boy and I am not interested in anything else.”

Hope and Homes for Children

Thank you

Thanks to your continued support, our team was able to support more children like Ivan – standing up for their right to a loving, family home. Today, the orphanage has been shut down. And that’s all thanks to your help.

Want to hear more incredible stories about the impact of your donations? Sign up to our Mailing List and receive more heartwarming and inspiring examples of children finding their way back to family.

Join the Mailing List

SUPPORT OUR WORK We need your help

Your donation will help us bring more children like Ivan back to family.

The post “It was the happiest day of my life, when I took my boy back” – Ivan* and Stoyan’s* story appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>The post “They said how could you possibly want to keep black children?” appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>By providing the practical and emotional support their parents needed, Hope and Homes for Children in Bulgaria made it possible for Kaloyan and Maria to be reunited with their family and grow-up where they belong; with the people who love them.

Four year-old twins Kaloyan are very much the centre of attention in the warm and happy home they share with their mum, Tanya, their stepdad Ivan and their older brother and sisters in a village in the North West of Bulgaria.

But the twins spent the first five months of their lives separated from their family in an orphanage after ill-health threatened to tear their family apart. Tanya became pregnant with the twins when she was working abroad to earn money for the family. Ivan agreed to stand by his wife, even though the babies were not his, and Kaloyan and Maria were born soon after Tanya returned home. It was a traumatic birth that ended in an emergency caesarean section and left Tanya suffering from post-natal depression. At the same time, Ivan was admitted to hospital to receive treatment for a heart condition.

Tanya felt completely alone. “I listened to the nurses in the hospital who behaved very badly. They said, “How can you even want to look at your black children? Better you give them up, right?”, she remembers.

Tanya felt completely alone. “I listened to the nurses in the hospital who behaved very badly.”

With no one to support her, Tanya felt she had no choice and made the heart-breaking decision to leave Kaloyan and Maria in an orphanage.

“I cried constantly when I signed to give them up because I grew up without a mother or a father. They left me very young, in a home and I just didn’t want my children to be the way I was.”

She returned home to Ivan and their older children but could not come to terms with losing the twins.

“I neither ate nor slept peacefully, just wondering how my kids were. How are they in this orphanage without me?”, she explains. Tanya was desperate to find a way to be reunited with her babies. And Ivan decided to support her decision. Even though everyone in their small rural community would know they were not his biological children, even though he was well aware of the prejudice they would face, he was determined to make their family whole again.

“I neither ate nor slept peacefully, just wondering how my kids were. How are they in this orphanage without me?”

It has been tough fight to overcome all the practical, bureaucratic and legal hurdles that have stood in their way—both to bring the twins home and to care for them ever since but our team in Bulgaria has been beside them all the way.

Social worker, Margarita Andreevksa, co-ordinates support for children in families in the area where they live. She ensured that Kaloyan and Maria’s family had all the practical and emotional support they needed to bring the twins home and be able to care for them for good. This included paying for transport for Tanya and Ivan to visit the twins in the institution and rebuild their bond with their babies; help with red tape to receive the extra social support the family is eligible to claim for the children; arranging and attending specialist appointments with Tanya to help her recover fully from the birth of the twins and protect herself from future unwanted pregnancy; securing the medicines that Ivan needs to manage his heart condition; and providing food, baby essentials, fuel for heating and extra clothes for all the children in the immediate months after the twins returned from the orphanage.

“Social worker, Margarita Andreevksa, co-ordinates support for children in families in the area where they live. She ensured that Kaloyan and Maria’s family had all the practical and emotional support they needed to bring the twins home and be able to care for them for good.”

Five months after they were born, Maria Andreevska went with Tanya to bring the twins home from the orphanage and in the months that followed she helped to arrange and attended their medical appointments to make sure they have treatment when needed and all the vaccines they need to enroll at nursery. Today Kalyon and Maria are four years old and they are happy, sociable and energetic children. Like all children their age, they love their toys but especially picture books that make sounds. Because of his health issues, Ivan does most of the childcare while Tanya works as a street cleaner. They both take seasonal work like picking walnuts where they can. “Everything was just wall after wall, after wall, after wall,” Ivan says, “But here we are and we are still one.”

Support our work Every child deserves a family

Help us to make sure that every child has a loving, stable home.

The post “They said how could you possibly want to keep black children?” appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>The post “I saw that Ana loved her children and she fought for them.” appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>The authorities thought both her children would be better off in an institution. But orphanages do not protect children, they harm them.

Consigning children to one-size-fits-all institutions, puts them at high risk of neglect and abuse and threatens their fundamental development. This is especially true for children as young as Vasilica and Ecaterina. To feel safe and happy, to grow, learn and really thrive, all children need to know that they are loved, and they belong; they need families.

Ana battled for two years to bring her children home again. Through our local partners, CCF Moldova, we made sure she had the practical and emotional support that she needed to succeed. “I saw that Ana loved her children and she fought for them,” says Natalia, the experienced social worker who stood by her, every step of the way.

In the orphanage, Vasilica spent long hours alone in a cot with no one to play with him, encourage him or love him. Today, reunited with his family, he’s a very active, much-loved little boy who likes building tall towers with his wooden blocks and playing chase with his sister.

Natalia is continuing to make sure that Ana has the specialist support and advice she needs to continue to care for Vasilica at home. Their next goal together is to make sure that he can attend nursery and then school, so that he can continue to learn and develop, alongside his sister and the other children in his community.

Support our work Help bring children home

With your support, we can reunite families torn apart by orphanages

The post “I saw that Ana loved her children and she fought for them.” appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>The post No child left behind: Pioneering programme proves all children can thrive in families appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>

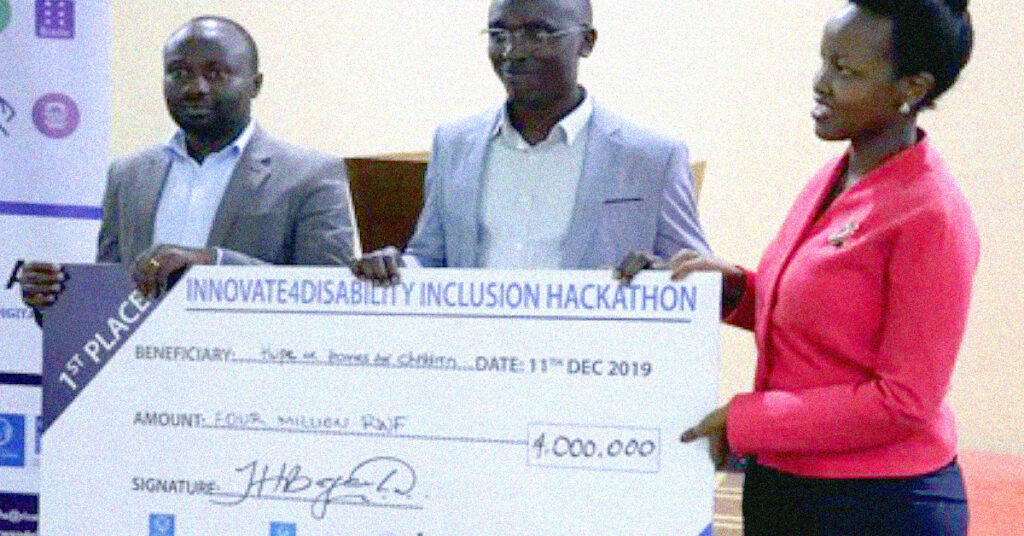

Implemented by Hope and Homes for Children in Rwanda and Child’s i Foundation in Uganda, the ‘No Child Left Behind’ programme was funded through the UK Aid Match programme.

Over three years, this pioneering project has reached 127,940 children and demonstrated, in two distinct national contexts, that it is possible for children with disabilities to live in loving family environments and in safe communities. The success of the programme shows that alternatives to institutional care can be inclusive and that this model is achievable in an African context, ensuring that no child is ever left behind. Carrol (above) is one such child; a little boy whose life has been transformed by this project.

“The success of the programme shows that alternatives to institutional care can be inclusive and that this model is achievable in an African context”

Between May 2018 and March 2021, the ‘No Child Left Behind’ programme successfully:

Closed an orphanage for children with disabilities in Rwanda

Supporting 26 children to live safely in family or community-based care. The institution has been transformed into a disability-inclusive Community Hub, equipped to respond to the specific needs of children with disabilities and their families. A further orphanage is under closure, having already transitioned 16 children and is progressing well on its way to becoming an inclusive Community Hub.

Closed three orphanages in Uganda

Supporting 105 children to move safely into family-based care, providing vital evidence and a practical blueprint for further reform. One has transformed to a Community Hub; the second has been replaced with outreach programmes to support vulnerable families in the community; and the third is in the process of being converted into a community centre.

Across both Rwanda and Uganda in the course of the programme we have:

- Trained 581 foster carers (including 273 specialist foster parents) to care for vulnerable children and children with disabilities

- Established 44 child protection and poverty reduction committees known as Community Development Networks (CDNs) and trained 2,808 CDN members and Community Volunteers. CDNs, made up of community and local authority representatives, provide strong referral and gatekeeping mechanisms that keep children safe in families

- Through these Community Development Networks, we have provided gatekeeping and prevention services to 132,046 children at risk of family separation, including 5,046 children with disabilities

- Of these, 5,707 children (including 1,012 children with disabilities) have been supported to remain safely with their families via our Active Family Support model, which builds family resilience and reduces the risk of babies and children entering orphanages

- Trained 55 government and NGO professionals to provide targeted support to children at risk of separation from their families

Crucially, the ‘No Child Left Behind’ programme has also helped to raise public awareness and challenge negative attitudes to disability. Community leaders and key local stakeholders have been engaged to champion family care for all children, and children with disabilities and their families have been empowered to form local peer support groups.

“Crucially, ‘No Child Left Behind’ has also helped to raise public awareness and challenge negative attitudes to disability”

At the same time, this pioneering project has increased understanding amongst national policy and decision-makers in both Rwanda and Uganda about the benefits of family-based care reform and community-based child protection mechanisms.

In March 2021, as the programme completed, outcomes and learning from ‘No Child Left Behind’ were shared at a regional conference on disability, organised by Hope and Homes for Children and the National Council of Persons with Disabilities, in Rwanda. Speaking at the event, Innocent Habimfura, our Regional Director for East and Southern Africa, concluded, “Every child deserves the love of a caring family and this programme has shown how, by closing institutions, supporting families to stay together and enhancing child protection systems at community level, we can make it possible for all children to enjoy their right to live in families.”

The post No child left behind: Pioneering programme proves all children can thrive in families appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>The post Children share experiences with UN to shape childcare appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>First-hand accounts from people living with disability

The work of Hope and Homes for Children in Rwanda has recently been the focus of attention for the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Through a number of online consultations starting in March, the United Nations Committee has been hearing first-hand accounts from children and adults living with disability, as well as from their representative organisations

“The United Nations Committee has been hearing first-hand accounts from children and adults living with disability”

Many disabled people experience isolation, lack of visibility and segregation. The United Nations Committee is working to ensure that everyone living with disability can live safely in their communities. However, one of the biggest barriers to inclusion is the use of orphanages—a common response to the needs of children with disabilities. Yet, with the right support, these children could instead grow up in the care of a loving family.

“One of the biggest barriers to inclusion is the use of orphanages—a common response to the needs of children with disabilities”

New set of childcare guidelines

Typically hosted in-person, but moved online this year due to Covid, the United Nations Committee is relying on these consultations to inform a new set of childcare guidelines being drawn up. By the end of the year, these guidelines will show how children with disabilities can be cared for in family and community settings—without the need for national and local authorities to ever resort to the use of orphanages.

Over the last few months, our team in Rwanda has been an observer at a number of these regional consultation events. In June, 170 individuals were invited to attend the session, with around 30 speakers sharing stories of their experience with all members of the United Nations Committee’s African delegation.

“In June, 170 individuals were invited to attend the session, with around 30 speakers sharing stories of their experience with all members of the United Nations Committee’s African delegation”

Reflections from care leavers in Rwanda and Kenya

One child we helped return to their parents in Rwanda had been confined to an institution for five years, simply because there weren’t the services in the community that offered their parents the right support to care for them. Now a young person, reflecting back on their experience they told the United Nations Committee that children are often abandoned, and their parents never visit them again. “The institutions that separate them from their families are not solution,” they claimed. “Having families is their right, being loved and supported is what children with disability need most, it is up to us all to strive for this, to advocate for this.”

Also taking part in the global consultation were two care leavers we supported in Kenya. One care leaver shared their concern at being “misunderstood and misrepresented.” As a result, children are unable to influence what happens around them. “It’s important the process of deinstitutionalisation is humanised,” they added. “Children with disabilities in institutions give up on themselves, compromising their wellbeing. Stigma, stereotyping and social taboos are a huge barrier to the reintegration of children with their families.”

“Stigma, stereotyping and social taboos are a huge barrier to the reintegration of children with their families.”

These invaluable insights from care leavers were accompanied by a written submission about our work supporting children with disabilities in Rwanda, providing the United Nations Committee with thorough and compelling insights to inform their childcare reform proposals.

Equipped with these insights, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is in a much stronger position to firmly instruct all UN member states later this year. The message is clear: institutions are never acceptable for any child.

Photo credit (top): Child Rights Connect

The post Children share experiences with UN to shape childcare appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>The post Protecting children with disabilities using SMS technology appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>In this blog post, Innocent Habimfura, Regional Director for East and Southern Africa, explains how SMS technology has revolutionised finding and supporting children with disabilities. This technology was piloted in both Rwanda and Uganda with help from the UK Aid Match programme.

It is a great injustice that children with disabilities are still subject to stigmatisation and discrimination. They are often perceived as bringing shame on families. So instead of seeking support, many families hide their disabled children away.

The problem: locating disabled children

It is vital to successfully locate children with disabilities, to ensure they and their families receive the support they need. This has been particularly challenging in remote, hard to reach communities.

The National Council of Persons with Disabilities (NCPD) and local authorities should have a constantly updating record of children with disabilities so they can then plan for and provide appropriate support. But this wasn’t happening. Although it’s likely that someone in the neighbourhood knows that a child with disabilities is hidden away, they previously had no way to inform the right authorities at no cost.

“Although it’s likely that someone in the neighbourhood knows that a child with disabilities is hidden away, they previously had no way to inform the right authorities at no cost.”

The solution: SMS technology

This is where the pilot of SMS (Short Message Service) technology in three districts has been so successful. SMS has been an effective way to report a child with disabilities facing protection concerns, as it allows anyone to send a free message to many service providers at the same time.

This then enables numerous organisations to take action in a more co-ordinated way. As a web-based application, it has encouraged information sharing, monitoring and referral of delicate cases.

Clearly there are many benefits, as SMS allows cost-effective two-way communication. A standard message can be sent to many organisations and individuals, a kind of top down approach. Aline, our Social Worker, told me: “It’s been practical to send SMS to targeted local authorities and community volunteers. We’ve been able to raise awareness on the rights of people with disabilities, to promote behaviour change.”

Conversely, messages can be sent from community volunteers to local authorities—an effective bottom-up approach. This has been particularly beneficial, as one NCPD staff member at district level told me:

“The SMS technology means we now have children and people with disabilities coming to us each and every day. We are discovering new people with complex needs. I used to be brought here and there to support other departments but now I provide all my time. Rather than working on a set of activities, I have to respond to demand rising from the ground. I feel proud to serve the real people in need.”

NCPD Staff member

Planning the cost of support for children with disabilities

With an increased number of children with disabilities becoming known to the local authorities, the budget allocated to support them can be informed by empirical, real demands.

The Executive Secretary of the NCPD explains: “This technology is the kind of solution we need. SMS tells us about a family or a person with disabilities and we can provide tangible solutions to them.

For the first time, there’s a tool that gathers enough information for accurate future planning rather than basing plans on imagination or biased estimation. With scarce resources, we are able to prioritise those with pressing needs. We have enough details to refer the case to a partner or service provider in the district, who can then design a specific intervention to empower the family or make the individual more resilient. It is about real life.”

Supporting families keeps children with disabilities safe at home

While the needs around disabilities are complex, we can record the data sent by communities on the SMS database. By analysing this data, our teams can then make recommendations and provide guidance to our partners on anything from health, education and shelter, to reintegration in communities and the provision of assistive devices such as wheelchairs. In this way we can address children’s needs and make a positive impact for families and communities.

“SMS data enables us to address children’s needs and make a positive impact for families and communities.”

Keeping everyone safe during COVID

There were other, unexpected benefits of the SMS technology too. Throughout the Covid pandemic, we’ve been sending messages to community volunteers on prevention measures, helping to combat the spread of disease. This was particularly important for vulnerable members of the community, including those with disabilities.

Now that we’ve successfully piloted SMS technology in three districts, several partners from Civil Society or government have asked how and when we can scale up to reach all 30 districts of Rwanda. Interest only keeps growing and now we must raise more funds to scale up in the remaining 27 districts.

As I claimed in my last blog post, when families have the right support, they make the greatest positive impact in the lives of children.

The post Protecting children with disabilities using SMS technology appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>The post No child left behind: closing orphanages for children with disabilities in Rwanda appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>Here, Innocent Habimfura, Hope and Homes for Children’s Regional Director for East and Southern Africa, looks back on an extraordinary journey to lay the foundations for inclusive childcare reform in Rwanda and beyond.

“Urabona ko abana bamerewe neza rwose. Barishimye” was a phrase I heard, repeated word for word, during the course of our three-year project to move children with disabilities from orphanages to families in Rwanda. In English this means, “It is clear for us to see how the children are doing great.” One time, I heard this from a high level official, visiting children who had returned to their families or joined foster families. Another time, an orphanage manager made the same observation with exactly the same words. Hearing those beautiful words repeated, brought back happy memories of childhood songs to me. I felt a sudden calmness in my soul, realising how much our three-year project had improved the lives of these children. Now they were thriving and developing in every way, at home in families, where they belonged.

“We simply need to recognise that the family has its own magic.”

I remember clearly, sitting and talking with the official, after visiting three children who were now living with families, after years in the orphanage in Gatsibo district. He was so surprised and impressed by the progress they’d made. The same thing happened a year later, when the nuns who ran the second pilot orphanage near Kigali, together with representatives from government agencies that were supporting the closures, came with us to visit the children who had so far been placed in families. I could see their unanimous agreement that this was the right choice for the children because they were all nodding silently in unison as they watched these children with their parents and siblings.

It’s impossible to list all the different ingredients that bring about this change, when a child returns to a family from an orphanage. We simply need to recognise that the family has its own magic.

The impossible became possible.

‘No Child Left Behind’ was more than a project, an activity, a deliverable; it became a change-making agent to transform the lives of children with disabilities, those living in institutions in particular. The pilot closures of institutions for children with disabilities and the transformation of those facilities into inclusive community hubs, has provided a model that is already informing the development of inclusive child protection systems in Rwanda and elsewhere. As one contributor to the conference that marked the end of the project put it, through ‘No Child Left Behind’ “the impossible became possible.”

Despite the best intentions of the orphanage manager and a small number of untrained staff, opportunities for the children to develop and thrive were non-existent.

Previous closure projects had provided sufficient evidence to our teams that it was urgent and important to support children with disabilities also, to leave orphanages and live in families. But convincing other stakeholders that this pilot project was necessary was very challenging. Our plan was clear. We needed to carry out two professional pilot closures, one in a rural area and the other in an urban setting, to inform future national plans for deinstitutionalisation.

Mama Kiki’s in Gatsibo district was the first orphanage targeted for closure.

Which orphanage to close?

As we began assessing potential institutions, officials from Gatsibo, a rural district in Rwanda’s Eastern Province took the first step. They were already committed to becoming a district free of orphanages and, working with the National Commission for Children, we had already succeeded in closing three institutions in the area. With the district’s support, we began working with the children, staff, families and wider community of the Wikwiheba Mwana institution, known locally as Mama Kiki’s. There were 19 children and seven young adults with a wide range of physical and learning disabilities, living together in poor conditions in this isolated facility. Despite the best intentions of the manager and a small number of untrained staff, opportunities for the children to develop and thrive were non-existent.

We made quick progress because Mama Kiki herself, the woman who had helped to set up and run the orphanage, was so positive and supportive about the change.

We carried out rigorous case-management to assess the children and young adults there and find the right alternative to the orphanage for each of them. Closing orphanages in this way cannot be rushed but, in this instance, we made relatively quick progress. This was largely because Mama Kiki herself, the woman who had helped to set up and run the orphanage, was so positive and supportive about the change. She had established the facility together with a group of other parents who were struggling to care for children with disabilities without the support they needed.

Cary had lived in the orphanage for years because her family could not care for her at home. She was desperate to be reunited with her mum and her brothers and sisters. By working with her family to address their concerns and provide the training and resources they needed, Cary became one of the first to leave the orphanage and return home.

Closing the first orphanage

After 15 months, on 19 November 2019, the 30th anniversary of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, the last two children left the Wikwiheba Mwana orphanage and the facility was closed. Straight away, work began to transform the buildings on the orphanage site into an inclusive community centre.

Closing an orphanage for children with disabilities in this way for the first time was a great achievement. When we took our partners and stakeholders to visit reunited families, everyone was impressed by the positive change, the progress made by the children when they realised they are back where they belong and by the implementation of well-designed care plans for each child. This raised a high interest and a feeling of emergency among those involved, to rescue all children remaining in institutions in Rwanda.

By coincidence, on the day the last two children left the orphanage in Gatsibo, the very first child began her new life beyond the gates of the Centre Incuti Zacu (CiZ) orphanage in the Rwandan capital, Kigali.

Closing orphanage number two

The choice of this second target closure was motivated by its location in the city but also its status as a well-known institution for children with disabilities. Closing CiZ meant a lot; in the course of the closure programme, children, parents, communities, church leaders, the media and the institutions’ many supporters would all be educated to protect and respect the rights of children with disabilities to be seen as individuals and to live in the love of a family.

Unsurprisingly, there was stiff resistance at the start but gradually the nuns who ran the orphanage became our allies.

The time spent on engagement and trust-building was not in vain. As the project progressed, it was so encouraging to see the sisters voluntarily begin to attend regular joint meetings with partners, take part in field activities and case management to improve the wellbeing of children in families and help to increase trust and reduce resistance among other stakeholders. And when it came to overcoming opposition, it is crucial to acknowledge the vital importance of the well-established and high-functioning partnership between Hope and Homes for Children, and the government agencies, the National Council of Persons with Disability (NCPD) and the National Child Development Agency. The role of NCPD was especially significant, through its existing relationships with, and coordinating function for all institutions for persons with disabilities Rwanda.

“The plan to transform the institution into an inclusive community centre was also welcomed with excitement”

The very first person to leave CiZ was a young woman called Lorette who had spent much of her life so far, trapped in the institution after she lost the lower part of one leg following an accident as a child. With the right support at last, she was able to fulfil her dream to leave the orphanage, reconnect with her family and study at university. In early 2021, she graduated with a degree in Applied Economics and is now beginning an independent life of her own.

Establishing new services to support the community

As the work of transitioning children and young adults from the orphanage into families and communities progressed, the plan to transform the institution into an inclusive community centre was also welcomed with excitement by all the stakeholders.

By establishing early child development (ECD) services and specialist services for children and young people with disabilities, we could support parents and other relatives to care for their children at home and still be able to work to provide for their families. With early detection of disabilities, children will receive timely support to overcome barriers and develop independent living skills. This model for an inclusive community centre will be replicated in other communities to ensure children with disabilities receive high quality support services in their own neighbourhoods, instead of being removed from their communities with false promises of access to specialist services in an institution. Commenting on the success of the ‘No Child Left Behind’ programme, the Minister in charge of social affairs rightly said, “We can’t talk about caring for people without observing their rights.”

Providing day care, early child development and other services through community hubs in the places where orphanages once stood, symbolises a lot; a paradigm shift from offering inadequate, unnecessary and harmful care for children to the provision of life changing, respectful and dignifying services, provided with a clear mission to help children stay with their families.

83% of children were reintegrated with their families. But what about the 17% for whom it was either not possible or not appropriate to return home?

Deinstitutionalisation has been simplified to mean reintegration programs, which call for the reunification of children with their original families. This still makes sense as the majority of children in institutions have at least one living parent or other close relative. And from both the pilot closures of institutions for children with disabilities, 83% of children were reintegrated with their families. But what about the 17% for whom it was either not possible or not appropriate to return home?

‘No Child Left Behind’ was conceived to develop a set of family-based care alternatives to meet the needs of each individual child and this included foster care, guardianship, domestic adoption, and for older teenagers and young adults, support to begin living independently.

In the course of the programme, over 465 foster carers, including 271 who are ready to open their hearts and homes to children with disabilities, were identified, selected and trained to welcome children in need of alternative care. Together, they constitute a powerful community-based resource, to prevent families having to rely on institutional care, with all its negative effects on child development and wellbeing.

Children and persons with disabilities continue to be the subject of stigmatisation and discrimination

Attending peer to peer groups’ discussions in the communities around the orphanages, confirmed to our team that some children and persons with disabilities continue to be the subject of stigmatisation and discrimination. These community-based groups—not limited to the parents of children with disabilities—include lending and saving groups and nutrition groups. They provide a safe place for members to share challenges and constructive testimonies. In our meetings we request group members to not hide their children with disabilities, to not lock them up when they have to work, which can lead to extreme neglect, a group member shared.

Disability and poverty are interlinked. Without tailored family support the situation for children in vulnerable families will worsen. As if this was not enough, the Coronavirus pandemic came to make the living conditions of families of children with disabilities even tougher. Providing direct support through our Active Family Support model has allowed us to mitigate the shock for many. We have supported children to access specialised medical treatments, backed some families to start small businesses to increase their income and supported others to renovate their homes and improve living conditions for their children. One mother told me repeatedly, drying her tears, “to be honest, we were considering our child as a burden, a problem. Now with all the advice and support we have received, this same child has become a blessing to all of us.”

The question we are asked now has changed from ‘Why do you close institutions?’ to ‘How can we close them?’

We are confident that the partnership established around ‘No Child Left Behind’, with the government taking full ownership of all the services developed, will have a positive and lasting impact on the lives of children. The research and practice models that were documented in the course of the programme, give us strong reason to believe that this three-year project has laid strong foundations for inclusive child protection and care reform in Rwanda. This in turn will serve as a reference for other countries with the political will to reform their child protection and care systems.

It is so rewarding that the question we are asked now has changed from “Why do you close institutions?” to “How can we close them?” What can be done to support children in families, to prevent their institutionalisation?

Although some critical issues of children with disabilities were addressed during the implementation of this project, we cannot say that all concerns were addressed. There is still much to be done but we feel confident that a great deal has been learned that will unlock future efforts to prioritise the wellbeing of children with disabilities, to ensure they receive the right support to thrive within families and inclusive communities.

All children need families, never orphanages. The institutionalisation of children is neither necessary nor acceptable and it should be avoided. When families have the right support, they make the greatest positive impact in the lives of children.

The post No child left behind: closing orphanages for children with disabilities in Rwanda appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>The post We demand states close down institutions for children and protect rights of Romani families appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>

The new European Union Strategy on the Rights of the Child states that all children, including those with disabilities and from disadvantaged groups, have an equal right to live with their families and in a community. Yet in many countries throughout Europe, Romani children are routinely removed from their families and placed in children’s homes at a disproportionate rate compared to the rest of the population. Research in Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Italy, Romania and Slovakia showed that Romani children can make up between 20- 80% of children in care institutions due to institutional biases, discrimination, and the illegal practice of removing children on the basis of poverty. This is a long-standing issue, which in light of the new strategy on the Rights of the Child, the new EU Roma Strategic Framework, and the EU anti-racism action plan, needs to be urgently addressed.

The organisations call on European Union institutions to continue to support member states, enlargement, and neighbourhood countries to break the cycle of poverty, combat discrimination, and promote national strategies to speed up de-institutionalisation reform, including by using EU funds. The organisations call on national governments, in countries inside and outside of the EU, to commit to eliminating institutional care and investing in accessible social support mechanisms, preventative measures, and family-based care for those children whose best interest is to be removed from their families of origin.

The ERRC is bringing legal complaints in seven countries (Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Moldova, North Macedonia, Romania, Slovakia, & Ukraine) which are institutionalising young children and discriminating against Romani families.

ERRC President, Đorđe Jovanović, said:

“We see the existence of these state homes as a form of violence against young children, and the discriminatory practice of filling them with Romani kids as a form of racist violence. These countries have made promises to close their institutions but progress has been too slow. If they refuse to modernise their care system, then legal action is the only option.”

The legal complaints are being taken before national equality bodies, ombudsperson’s offices, and international bodies such as the European Committee of Social Rights. The complaints are based on research carried out mostly in 2020 and 2021 into the overrepresentation of Roma in state care. They are designed to hold states accountable fortheir obligations under international law to respect the right of the child to family relations, and to ensure that the best interest of the child prevails at all times.

Mark Waddington CBE, Chief Executive Officer at Hope and Homes for Children, said:

“Any form of institutionalisation based on discrimination is a breach of human rights. We are working tirelessly across the world to ensure that no child ever suffers the harm of institutions and instead grows up in a loving family. It’s essential that European states act now to do the same”.

Institutionalisation has devastating emotional and developmental effects on children, especially their physical growth, cognition, and attention, as well as their ability to form attachments. The effects of institutionalisation on infants – particularly in the early stages of life – can be largely irreversible.

Institutionalisation has an especially negative effect on Romani children who leave care stigmatised both for their ethnicity and for being an ‘institution child’. The chances of children being reunited with their family of origin drop exponentially with every year in care, as do their chances of being adopted. The adoption of Romani children living in institutions is almost non-existent, due to societal racism and a lack of parents willing to adopt Roma in many countries.

A human rights-compliant response to the existing situation of Romani children in state care calls for the total elimination of institutional care, and the development of appropriate child support services across Europe. We call on states to provide full and adequate protection to Romani children and families at risk of separation, to fully ensure that child removal on the basis of poverty is prohibited in law and in practice.

*This work is supported by Clifford Chance

This press release is also available in Bulgarian, Macedonian, Romanian, Slovak and Ukrainian.

For more information, or to arrange an interview contact:

Jonathan Lee

Advocacy & Communications Manager

European Roma Rights Centre

jonathan.lee@errc.org

+36 30 500 2118

Michela Costa

Director of Global and EU Advocacy

Hope and Homes for Children

michela.costa@hopeandhomes.org

Ally Dunhill

Head of Advocacy Eurochild

Ally.Dunhill@Eurochild.org

+32 02 211 0558

The post We demand states close down institutions for children and protect rights of Romani families appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>