Here are tips to tell your volunteering story on social media, using language and images to make a positive impact and break stereotypes, not reinforce them.

The post A guide for volunteers and travellers: 4 principles to promote dignity and break stereotypes on social media appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>Volunteer tourism, or voluntourism, is an emerging trend of travel linked to “doing good”. Volunteering programs are expanding rapidly as it has been estimated that every year 1.6 million people volunteer overseas, with voluntourism being considered the fastest growing ‘trend’ in travel, a trend worth an estimated $2.6 billion per year.

In the right circumstances, volunteer tourism provides significant benefits for both the volunteers and the communities that receive them. But we need to be absolutely clear: volunteering in an orphanage abroad is a bad idea.

We know that volunteers and tourists generally have great intentions when travelling. So when you are abroad, it’s worth considering how you tell your story on social media, to make sure you use language and images to make a positive impact and break stereotypes, not reinforce them.

Dignity and respect for people in your insta feed

Within our Safeguarding Policy we have a chapter on the use of images (both photographs and video) and stories. Our overriding principle is to maintain the safety, privacy and dignity of children, families and communities portrayed.

When you’re volunteering or travelling abroad, you too can ensure that the images you use and messages you write enforce:

- Respect for the dignity of the people you meet

- Belief in the equality of all people

- Acceptance of the need to promote fairness, solidarity and justice

Some concepts from our “Guidelines for publishing images and stories” that could be useful to consider when you’re documenting your travels and experiences:

Informed consent

We must obtain informed written consent from any person we wish to photograph, video or interview, regardless of whether or not they are identifiable in the image. The written consent should as a rule be acquired PRIOR to capturing their image or filming them and contributors should be given sufficient information and time to reflect between consent being requested and pictures/interviews being taken

Children and adults in the care system

Children in the care system, and especially those in institutional care, are particularly vulnerable and therefore need a higher level of protection. Being institutionalised has a negative impact on their lives and this can be exacerbated by being discriminated against because of their early life in care.

Highlight positive and transformative effect

We should endeavour to show the positive and transformative effect of our work. Wherever possible, images and stories of institutions, or images/stories that illustrate the need, should not be used in isolation, but balanced with positive images and stories, showing how we are transforming lives.

Portraying diversity

As in all our communication publications, videos and website, we should ensure there is a balanced representation of the wide range of people we work with.

The social media guide for volunteers and travellers

Radi-Aid is an annual awareness campaign created by the Norwegian Students’ and Academics’ Assistance Fund (SAIH). Emerging from the satirical campaign and music video ‘Radi-Aid: Africa for Norway’, the campaign has focused on arranging the Radi-Aid Awards (2013-2017), celebrating the best – and the worst – of development fundraising videos. Along with this, they have produced several satirical, awareness-raising videos. In 2017, they have also developed the below Social Media Guide for Volunteers and Travelers.

“An increasing number of people spend their holidays or gap years traveling, while at the same time doing something meaningful and different. Language and images can either divide and make stereotypical descriptions – or unify, clarify and create nuanced descriptions of the complex world we live in. It can be difficult to present other people and the surroundings accurately in a brief social media post. Even though harm is not intended, many volunteers and travelers end up sharing images and text that portray local residents as passive, helpless and pitiful – feeding the stereotypical imagery instead of breaking them down. This is your go-to guide before and during your trip. Use these four guiding principles to ensure that you avoid the erosion of dignity and respect the right to privacy while documenting your experiences abroad.”

PRINCIPLE 1: PROMOTE DIGNITY

Promoting dignity is often ignored once you set foot in another country, particularly developing countries. This often comes from sweeping generalizations of entire people groups, cultures, and countries. Avoid using words that demoralize or further propagate stereotypes. You have the responsibility and power to make sure that what you write and post does not deprive the dignity of the people you interact with. Always keep in mind that people are not tourist attractions.

PRINCIPLE 2: GAIN INFORMED CONSENT

Informed consent is a key element in responsible portrayal of others on social media. Respect other people’s privacy and ask for permission if you want to take photos and share them on social media or elsewhere. Avoid taking pictures of people in vulnerable or degrading positions, including hospitals and other health care facilities. Specific care is needed when taking and sharing photographs of and with children, involving the consent of their parents, caretakers or guardians, while also listening to and respecting the child’s voice and right to be heard.

PRINCIPLE 3: QUESTION YOUR INTENTIONS

Why do you travel and volunteer? Is it for yourself or do you really want to make a difference? Your intentions might affect how you present your experiences and surroundings on social media, for instance by representing the context you are in as more “exotic” and foreign than it might be. Ask yourself why you are sharing what you are sharing. Are you the most relevant person in this setting? Good intentions, such as raising awareness of the issues you are seeing, or raising funds for the organization you are volunteering with, is no excuse to disregard people’s privacy or dignity.

PRINCIPLE 4: USE YOUR CHANCE – BRING DOWN STEREOTYPES

When you travel you have two choices: 1. Tell your friends and family a stereotypical story, confirming their assumptions instead of challenging them. 2. Give them nuanced information, talk about complexities, or tell something different than the one-sided story about poverty and pity. Use your chance to tell your friends and stalkers on social media the stories that are yet to be told. Portray people in ways that can enhance the feeling of solidarity and connection. A good way forward is to ask the local experts what kind of stories from their life, hometown, or country they would like to share with the world.

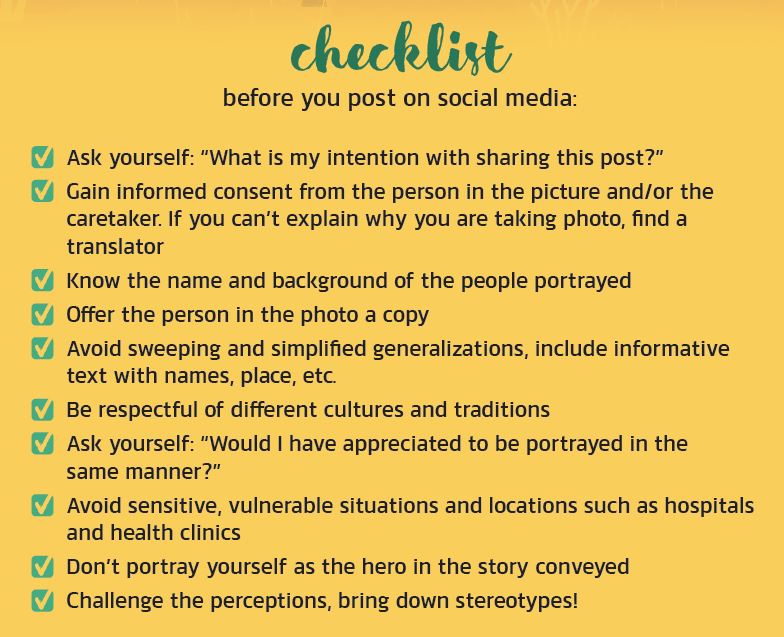

Here’s the social media checklist for volunteers and travellers from Radi-Aid, Africa for Norway:

You can download the guide at this link.

How to choose the right volunteering opportunity

If you’re thinking about volunteering abroad, here’s what to look for to make sure your time overseas is genuinely spent making a difference: check out this 10-point checklist to make sure you know what to look out for when you select your volunteering program abroad.

Help us #EndOrphanageTourism

Sign the pledge now

#EndOrphanageTourism – campaign against child trafficking and slavery in orphanages

The post A guide for volunteers and travellers: 4 principles to promote dignity and break stereotypes on social media appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>The post Want to volunteer abroad? Here’s your Volunteering 10-point checklist appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>Most people who volunteer overseas genuinely want to do something meaningful and experience a new culture. However, some of the companies that arrange this type of travel may be more concerned with creating a ‘life-changing’ experience for their customers, rather than responding appropriately to the needs of the host communities.

This is a particular problem when volunteers are offered the chance to work with vulnerable children living in orphanages and other institutions. Hope and Homes for Children, as part of the coalition, Rethink Orphanages, is working to raise awareness about the negative impact on children of volunteers and tourists visiting orphanages – read more about this campaign.

In short, our message is that it’s good to volunteer, but not in orphanages. There are other, better ways to make a real difference to children’s lives and learn about different cultures.

VOLUNTEERING 10–POINT CHECKLIST

If you’re thinking about volunteering abroad, here’s what to look for to make sure your time overseas is genuinely spent making a difference:

About the volunteering opportunity

– The needs have been set out by the local community.

Find out why the volunteer project has been set up and why volunteers are needed. As much as possible, the project should be directed and run by local people.

– It’s sustainable

Projects shouldn’t create a long-term dependency on volunteers. Ask what happens to the project when the volunteers go home.

– There’s no local alternative

Sometimes, volunteering can have a negative impact on local employment opportunities. Always look for projects where volunteers are brought in to enhance local capacity, e.g. to provide training or meet a short-term skills gap working with local people.

– It doesn’t involve ‘orphans’ or vulnerable children

Despite the best intentions of volunteers who want to care for children, it can do more harm than good. Children who live in orphanages are quick to form relationships with volunteers as they arrive, only to feel abandoned once again when they leave. What’s more, an estimated 80% are not actually orphans and have at least one living parent.

About you

– There’s a skills match

Think about what skills you have to offer that will be of use to the local community. Skills often in high demand include digital (websites, coding, social media), monitoring and evaluation skills, photography, fundraising (writing and submitting funding applications) language and computer skills. Don’t be tempted by volunteering placements for which you are not skilled or qualified – e.g. teaching or caring for children or providing medical care.

– It adds value

Look for opportunities where you will learn. When you return home, use what you have learned to engage in your own community or apply it to your career. Employers will be interested in evidence of impact, not just the fact that you have volunteered overseas.

About the volunteering-sending company

– There’s evidence of impact

Look to see if the company you will be travelling with has a proven track record. Find out what’s been achieved in the past by staff and volunteers and how projects are monitored and evaluated.

– You’ll be safe

Some volunteer-sending companies simply recruit volunteers for third parties, whereas others recruit volunteers for projects they manage themselves. Make sure you know who will be responsible for your safety, and who will be the point of contact for you and your family should anything go wrong.

– You’re not being ‘sold to’

Some companies use emotive language to entice volunteers to sign up with them. Avoid companies that talk about volunteers ‘saving the world’, ‘giving children the love they need’ or focus heavily on the travel and tourism elements of the trip. Instead, look for emphasis on partnerships and sustainability.

– You must apply to volunteer

The role of the volunteer-sending operator is to match your skills with the right project. You should expect to go through an application process and be vetted, as you would if you were applying for a job or university. You should also receive pre-departure support, including a briefing and possibly training and a job description about your volunteer placement.

Find out more about voluntourism here

The post Want to volunteer abroad? Here’s your Volunteering 10-point checklist appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>The post What’s wrong with visiting and volunteering in orphanages? appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>Volunteer tourism, or ‘voluntourism’, is travel trend linked to ‘having fun / doing good’. Every year approximately 1.6 million people volunteer overseas, with voluntourism being considered the fastest growing ‘trend’ in travel, worth an estimated $2.6 billion per year.

Good intentions have disastrous outcomes

For the most part, voluntourists are well-intentioned people, looking for an opportunity to travel and contribute to the countries they visit. Sadly though, when it comes to volunteering in orphanages, these volunteers risk harming rather than helping children.

Can volunteering abroad be positive?

In the right circumstances, volunteer tourism provides significant benefits for both volunteers and communities that receive them. But we must be absolutely clear: volunteering in children’s institutions is a bad idea.

Ask yourself this: would you be happy for a volunteer from overseas, with no experience and no background checks, to help out at your local school or nursery?

I think I can guess your answer. Yet this is exactly what’s happening in when foreign volunteers work in orphanages abroad. What many volunteers don’t know is that around 80% of the 5.4 million children housed in orphanages, are not orphans at all. Most are separated from their families because of poverty, disability or discrimination. Once confined to these large and loveless facilities, even babies and very young children are deprived of the vital one-to-one care and attention that every child needs to develop properly and to thrive.

100 years of research – orphanages harm children

Years of robust research show that institutions harm children. The lack of individual love that is characteristic of institutional care, damages children’s emotional, physical and neurological development. The results can last a lifetime. Yet, with the growth of volunteer tourism or ‘voluntourism’, there’s an increasing trend for people, often young and from higher income countries, to spend time helping in orphanages in other parts of the world.

Watch the short interview below “Voluntourism: More harm than good” with Leigh Mathews co-founder of the cross-sector coalition, ReThink Orphanages

Voluntourism in orphanages leaves children vulnerable to abuse where child protection regulations are lax. It creates attachment problems in children; they become close to short-term visitors. And it perpetuates the myth that many of these children are orphans in need of adoption.

Orphanage voluntourism and orphanage tourism: What’s the difference?

In many countries, Children in orphanages are exploited as ‘attractions’ for tourists. This perpetuates the orphanage economy and allows the proliferation and sustainment of institutions. This is “Orphanage Tourism”; tourist visits to orphanages as part of packages, day trip excursions or tours. The impact on children can be critical because of the cyclical, short-term nature of the visits and the experience of being treated as a tourist attraction. The need to attract tourists to visit orphanages can even mean children are purposefully kept in poor conditions. They can be denied food, clothing and other essentials in order to attract more money from visitors.

In this light, orphanage tourism can be seen as a form of child exploitation

This short animation shows the impact that volunteers have on children in orphanages from a child’s point of view.

The Love You Give campaign—take the volunteering pledge

As members of the coalition, Rethink Orphanages, we’ve added our voice to The Love You Give, #ChangeVolunteering campaign. It aims to raise awareness among young people about the negative effects of volunteering in orphanages.

Take the volunteering pledge at this link: “I pledge to not volunteer in orphanages and change volunteering for the better.”

It’s good to volunteer. But do your research first

We don’t want to discourage volunteering abroad. But we must alert people to the risk of volunteering in children’s institutions.

Most people who volunteer overseas genuinely want to do something meaningful and experience a new culture. However some of the companies that arrange this type of travel may be more concerned with creating a ‘life-changing’ experience for their customers, rather than responding appropriately to the needs of the host communities.

To ensure your time overseas is spent making a real difference, think about

- the volunteer company you use

- the volunteering program

- and the skills you yourself can bring to the project.

Want to help? Make sure your holiday won't harm anyone

Discover our 10 point checklist for volunteering abroad

The post What’s wrong with visiting and volunteering in orphanages? appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>The post More than food and shelter:<br>The importance of children’s social needs appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>It’s wrong, they argued, to treat belonging as little more than a ‘nice to have.’ So infuential was their work, the International Society for Self and Identity recently claimed Baumeister and Leary had “identified the invisible hand that guides much of the research in social psychology.”

In this exclusive blog, co-author of the original paper Mark Leary, PhD (Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, Duke University) explains why orphanages damage children by starving them of something just as vital as air and water.

Human beings are perhaps the most gregarious creatures on earth. Many other animals live with other members of their species in herds, flocks, hives, and troops, but human beings are more pervasively—some might say compulsively—social than any other animal. The reason is clear: Because they lacked speed, ferocity, and special abilities (such as the ability to fly, burrow, or clamber through treetops), our prehuman ancestors could obtain food and evade predators only by sticking together and relying on one another. As a result, human beings developed not only a motive to hang around with other people but also an exceptionally strong desire to belong to social groups, to be accepted, and to forge co-operative relationships with other people.

My research for the past 30 years has focused on how these fundamental social motives affect our thoughts, emotions, and behaviour on a daily basis and how the failure to satisfy these social needs undermines psychological wellbeing for adults and children alike. Not only does our desire for acceptance and belonging influence much of what we do—and, perhaps more importantly, much of what we don’t do—but research shows that insufficient acceptance and belonging lead to negative emotions (such as hurt feelings, sadness, loneliness, and sometimes anger), lowers self-esteem, and diminishes our quality of life. Furthermore, people sometimes behave in maladaptive and even antisocial ways when they feel inadequately accepted or that they don’t belong.

“Human beings developed not only a motive to hang around with other people but also an exceptionally strong desire to belong to social groups, to be accepted”

The social psychology of acceptance and belonging is relevant to understanding the plight of children who live in orphanages. Children who grow up in orphanages miss essential social experiences that lower the quality of their lives, impede their psychological and social development, and undermine their wellbeing. To understand these effects, let’s distinguish among four distinct interpersonal processes that are often confused.

First, to function normally, people must have some minimal level of social interaction with others. True isolation—as in the case of solitary confinement or being stranded on a desert island—obviously causes great psychological distress. But simply having fewer social interactions than we desire can also be distressing and disorientating, as many of us have experienced during the pandemic. Feeling socially isolated is associated with depression, sleep disturbances, problems thinking clearly, and indictors of poor physical health such as impaired cardiovascular function and lowered immunity.

“Children who grow up in orphanages miss essential social experiences that lower the quality of their lives, impede their psychological and social development, and undermine their wellbeing.”

But simply interacting with other people is not enough. You could spend all day, every day, talking to an endless stream of people passing through a large airport yet not feel that your social needs are being met. Although interacting with other people is often interesting, enjoyable, or an escape from boredom, we often interact with other people because those social interactions provide us with things that help us in one way or another, what behavioral researchers call “social provisions.” For example, other people provide us with information, advice, companionship, safety, emotional support, and practical help.

Most of these goodies come from people with whom we have positive, ongoing relationships, such as family members, friends, romantic partners, fellow group members, and co-workers. Not only do such people provide us with many things that we need, but merely knowing that supportive people exist in our life provides us with a sense of security even if we don’t interact with them much. Ongoing supportive relationships often operate like a volunteer fire department, standing ready to respond when called.

“Most of these goodies come from people with whom we have positive, ongoing relationships… merely knowing that supportive people exist in our life provides us with a sense of security even if we don’t interact with them much.”

In addition to needing to interact with other people and to have some close, supportive relationships, people also want to belong to various groups, whether they are friendship cliques, special interest groups, athletic teams, task-oriented groups at work or in the community, religious groups, volunteer organizations, or whatever. Belonging to groups not only provides contact with other people, some of whom may become supportive friends, but collaborating with others on shared goals also gives us a way to have an impact and provides a sense of purpose. Groups also provide a basis for much of our identity. These groups are important to our sense of who we are. In fact, when people are asked to tell others about themselves, they often refer to their group memberships.

So, people need social interaction, social support, and belonging, but even those are not enough for optimal wellbeing. People must also believe that they have high relational value to at least a few people in their lives—and, up to a point, the more, the better. Relational value refers to the degree to which people value having a relationship with us. The majority of people with whom we interact don’t value their relationship with us at all, even if they may enjoy chatting with us from time to time. Some people do value their relationship with us a little, but they wouldn’t be terribly upset if they never saw us again. They like us fine, but we’re expendable. Fortunately, most of us have a small subset of relationships in which we know that the other person deeply values their relationship with us, works to maintain it, and would be deeply troubled if our relationship ended.

No matter how much people interact with others, how much support they receive, or how many groups they belong to, people who believe that no one values having a relationship with them suffer deeply. They go through life feeling rejected and lonely, view their life as less meaningful, have fewer positive experiences, and typically perceive themselves more negatively. (After all, if no one values having relationships with me, perhaps something is wrong with me.)

“People who believe that no one values having a relationship with them suffer deeply. They go through life feeling rejected and lonely, view their life as less meaningful”

These four factors operate for everyone: we all need adequate levels of social interaction, social support, belonging, and relational value. But these experiences are often in short supply for children living in orphanages, particularly when we compare their experiences to the lives of children who grow up in a family setting. Although some families are dysfunctional in ways that undermine their positive impact on children, most families provide notably more social interaction (at least with adults), social support, belonging, and relational value than even the best orphanages can manage. And these effects extend beyond the immediate family setting as children form relationships with members of their extended family—especially grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins—as well as social connections with neighbours, their parents’ friends, their parents’ friends’ children, peers in the community, and others. Furthermore, these relationships tend to be more stable than those with staff, volunteers and other children in orphanages, who are more likely to come and go over time.

“We all need adequate levels of social interaction, social support, belonging, and relational value. But these experiences are often in short supply for children living in orphanages”

All of us need at least a minimum number of lasting, positive, and significant interpersonal relationships that provide us with adequate interaction, support, belonging, and relational value. Children are far more likely to develop such relationships in caring families than in orphanages.

Mark Leary, PhD is a a social and personality psychologist, and the editor of Character and Context, the blog site of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology.

Support vulnerable children

We’re fighting to make orphanages a thing of the past – and to make sure that every child receives the love and care they need to thrive.

The post More than food and shelter:<br>The importance of children’s social needs appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>The post How many children are there in orphanages around the world? appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>Ending orphanage care

Since 2005, I’ve worked with some of the world’s most marginalised children, striving for child protection and care systems that support children to thrive – from Rwanda to Bulgaria to Latin America. Passionate about evidence-based policy and practice, I have been privileged to lead national and regional care reform programmes in which our research has contributed to ground-breaking change.

Why is counting the numbers of children in orphanages important?

For example, in partnership with the Government of Rwanda, our 2012 national survey of institutions found 3,323 children living in 33 institutions. We also collected data around the characteristics of the children, as well as how and why they were sent to orphanages. Combined with evidence from our programmes and insights from our pilot closure of the Mpore Pefa institution, this gave the Government of Rwanda the information they needed to plan a route away from orphanages and towards family and community based care for all children. Indeed, Rwanda’s National Strategy for Child Care Reform is the first of its kind in Sub-Saharan Africa.

More recently, I found care leavers in Latin America eager to speak truth to power about the realities of children’s lives in institutions and the challenges of leaving the child protection system and living independently as adults. Their testimonies provide powerful evidence that governments must dramatically improve support for care leavers and eliminate institutions once and for all.

How can research help to close orphanages?

Now I have taken up a new post as Senior Strategic Research Partner, my job is to lead our global efforts to build research, evidence and insights so we can achieve our mission to catalyse child care reform across the world.

Research seeks to answer unanswered questions. Over time, those questions and answers may be refined, bringing new or different data, perspectives and contexts into play. With a curious mind, we will always be able to learn and understand more – and this curiosity is leading us to ask more questions at Hope and Homes for Children. One question that we hear frequently is:

“So, how many children really live in orphanages around the world?”

For many years, we used the figure of 8 million children living in institutions as it was based on the best available estimates from Save the Children. Today we can say that we know more about the scale of institutionalisation, thanks to Dr Chris Desmond and his team. Their global enumeration study provides the most recent and robust global estimates of children living in institutions. An estimated 5.4 million children live in institutions around the world. Sadly, this change does not represent progress towards deinstitutionalisation; the figure is the median average of a range of statistical estimates ranging from 3 to over 9 million children.

The truth is that we don’t really know how many children are living in orphanages worldwide, due to the lack of reliable data collection in many countries and the large proportion of unregistered institutions. We believe that even 5.4m is a conservative total estimate; the true number could well be higher.

Discounted, hidden and forgotten.

This lack of robust data is further proof of the way children in orphanages are discounted, hidden and forgotten, often warehoused in unlicensed, unregulated institutions. Still, this estimate paints a powerful picture of the scale of the issue. It helps evidence-led organisations like us to progress reform of child care systems and dramatically reduce the number of them.

What we know: orphanages harm children

When it comes to the impact of institutionalisation on children’s development, we can confidently say that a strong body of evidence shows that orphanages harm children. Under the Lancet Commission a group of academic experts in child health and mental health undertook a meta-analysis of 65 years’ worth of research on the development of children raised in institutions. It was a sizeable undertaking, analysing both quantitative and qualitative data from over 300 studies, carried out in over 60 countries with more than 100,000 children, of whom almost half have lived or are currently living in institutions. What this showed is that growing up in an institution is strongly linked with negative impacts on children’s development, including

- their physical growth,

- cognition,

- attention,

- ability to form attachments,

- socio-emotional development

- and mental health.

The Lancet Commission shows that moving to family based care can help repair some of this harm, especially earlier in life. But the longer children spend in institutional care, the greater the likelihood of negative impact and the smaller the chance of recovery.

There is also a growing body of evidence that institutions are not only harmful to children whilst in the institution, they generate lifelong repercussions when they leave care as young adults and perpetuate intergenerational poverty.

Our body of practice

Over two decades, we’ve built a body of practice and expertise in how to reform child care systems. We now see an opportunity to harness the data, evidence and insights to help illuminate the challenges and solutions we face, in the global drive to eliminate institutional care.

An evidence-driven organisation since our early days

Our founders Mark and Caroline Cook listened to children in Bjelave orphanage in Bosnia who shared their experiences and told them that they did not want to live in the orphanage, they wanted a family. Their testimony was powerful evidence of what children value, and we have responded to this evidence – as well as the testimony from thousands of children without parental care around the world who want the same thing. As well as valuing this evidence from children themselves, we have a history of producing expert programmatic evidence spanning all the regions we work in – from research into the situation of baby homes in Ukraine, children with disabilities in Rwanda, and care leavers in Latin America to name just a few.

Care reform needs robust evidence

Care system reform is a complex process which must be informed by robust evidence. In striving to meet the best interests of children, we must listen to them like our founders did. And we must go further to ensure that a diverse range of robust and rigorous evidence informs our approach to children’s care. The challenge ahead for us is an exciting one! I look forward to figuring out the knowns and unknowns, working closely with our talented teams on the ground, with academic partners and the growing community of researchers, NGOs, development partners and activists dedicated to generating and sharing evidence on how best to look after the world’s children. Evidence that shows not only the harm caused by institutionalisation and inaction – but the benefits gained for all by ensuring safe, loving families, responsive child protection and resilient communities.

Our Impact Orphanages harm children

We know that orphanages harm children. They also harm society.

The post How many children are there in orphanages around the world? appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>The post What is institutional care? appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>Despite decades of evidence showing how institutional care is profoundly damaging for children, it’s still difficult to provide a clear, all-encompassing definition of “institutional care of children”.

Commonly used terms include ‘institutions’, ‘orphanages’, or ‘children’s homes’. Whatever they’re called, even the best-resourced institutions cannot replace the nurturing and individualised care that a child needs, and a loving family can provide.

What is ‘Institutional Care’?

‘Institutional care’ is a type of residential care for large groups of children. It is characterised by a one-size-fits-all approach according to which the same service is provided to all children irrespective of their age, gender, abilities, needs and reasons for separation from parents.

The service provision is depersonalised and strict routines are followed to enable a small number of staff to deliver basic services. Children living in institutions, also known as orphanages, are isolated from the community, often far from their place of origin and unable to maintain a relationship with their parents and extended families. Siblings are often separated and children are segregated on the basis of age, gender and disability.

‘Institutional care’ is an oxymoron – institutions cannot by definition care for children

What are the 13 characteristics of orphanages?

Besides being residential facilities, one of the most frequently cited characteristics of institutional care is its size, meaning the number of places available for children in any given facility. The larger the setting, the fewer the chances to guarantee individualised care for children in a family-like environment, and the higher the chances for certain dynamics to appear.

However, size is only one indicator. There are other fundamental features. Institutional care can usually be identified by the presence of several of the characteristics described below, across the three areas: care provision, family and social relationships, and systemic impact.

Care provision

1. In institutions, the delivery of care and protection is inadequate. Children experience

- delays in their emotional, cognitive and physical development

- heightened risk of developing challenging behaviours and being victims of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse.

- A lack of suitable individualised care that responds to the needs and circumstances of each and every child.

- a regimented routine, which results in children following a prescribed daily schedule with little flexibility.

2. Living in an institution, by its own nature, leads to depersonalisation, reducing children to a file in the system. Children are

- ‘processed’ in groups according to a fixed timetable, without consideration for privacy or individuality. The result is children sleeping, eating, playing, and sometimes even going to the bathroom at the same time or in a set order, regardless of their individual needs.

- not encouraged or supported to develop and show their personal preferences and individuality. Clothes, towels and toys are often shared within the group and living space doesn’t allow for privacy.

3. The inadequate ratio of carers to children and the nature of their interaction is typical of institutional care. Children usually experience multiple caregivers throughout their stay and even on a daily basis. The instability and insufficiency of caregiving deprives the child of the opportunity to form a healthy attachment with a significant adult, which in turn leads to attachment disorders and difficulties with a wide variety of social relationships in later life.

4. Institutional care is utterly disempowering and fails to provide children with a basic set of practical and life skills required to live independently. Young people in institutional care often lack experience in

- preparing food,

- cleaning,

- making their own bed

- or managing personal finance, such as pocket money.

When leaving institutional care, they are faced with living an independent life in a world for which they are utterly unprepared.

Family and social relationships

5. The way institutions operate fails to support the development of strong and meaningful relationships between children, their parents and siblings, and the wider family. Around 80% of children in institutional care are not orphans, but they have very little or no connection with their families. Groups of siblings are often split up and sent to separate units, or even to other orphanages at different and sometimes distant locations.

6. Institutions tend to be isolated from mainstream communities, sometimes located in remote places. This segregates children in them from society even further, and the isolation stops them from learning relevant skills for living in communities, or gaining knowledge of their cultural heritage, traditions and values.

Geographical isolation was and is a particular feature of institutions for children with disabilities or challenging behaviour in Central and Eastern Europe and Commonwealth nations, with institutions purposely built or located in old, inadequate buildings away from broader society.

7. Social isolation is a common element. In the most closed and isolated environments, children’s entire lives are spent within the institution – including their education, leisure and healthcare. Even in relatively open structures, for example where children go to the local school, institutional care fails to provide a sense of ordinary life and belonging to the community. Institutionalised children usually lack adequate resources and professional support and have weak or no representation in schools. As a result, they tend to be stigmatised and perceived as ‘different’, which in turn leads to further marginalisation and exclusion.

Moreover, orphanages often segregate children according to age, gender, disability or other requirement, leading.

Systemic impact

8. Institutions also affect wider societal systems: their very existence influences the way that authorities, professionals and communities operate and how they identify and support children who are perceived as being at risk. They create a ‘pull effect’, offering local authorities and professionals an easy option for dealing with children and families in crisis.

9. Orphanages are often the only available and promoted service at community level, where local authorities and professionals can easily place children without parental care. In some contexts it is also wrongly perceived as being the safest option for babies and very young children in need of alternative care, including orphaned or abandoned new-born babies, premature babies or those identified as having additional needs or impairments.

10. Across the world, placing their child in an institution is the only way for families to access education or health services. It’s not uncommon for one child from a family to be sent to an orphanage for school, or to get medical care or other services. Equally, children failing in mainstream education are often sent to institutions which specialise in education for children with learning disabilities.

11. ‘Specialist’ institutions are largely perceived as the best option for children with disabilities, often at the advice of a doctor or institution manager. Parents lacking information, counselling and access to medical and support services will often turn to orphanages as their only available option. Children with disabilities or additional needs tend to stay in the institution for their entire life or are moved into facilities for adults.

12. In some cases, children are deliberately separated from their families and placed in institutional care to attract fee-paying volunteers and donors, or to maintain the system in existence, ensuring the employment of those working there. In the worst instances, children are also kept in poor conditions to elicit more sympathy and donations. Volunteering in orphanages for limited periods of time also contributes to the repeated sense of abandonment already felt by the children. The lack of background checks on visitors and volunteers exposes children to an increased risk of abuse and exploitation.

13. Institutional care for babies falsely creates the impression that there are numerous babies and young, healthy children in need of adoption. Over the past 20 years, whilst international adoption has continued to flourish, so has the evidence showing that babies in institutional care in many countries have been systematically bought, coerced and stolen from their birth families.

Get involved Help us protect children

The State is ultimately responsible for children’s rights. But private and institutional donors can stop funding orphanages – and fund care reform charities like ours instead.

The post What is institutional care? appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>The post Orphanages are the problem appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>Across the world, in a variety of contexts, orphanages are still widely misunderstood. Information has been slow to reach the general public. As a result, there are lots of misconception about institutions.

The most prevalent myth is that orphanages care for orphan children.

Well-meaning individuals and organisations commonly fundraise to support children in orphanages in lower-income countries. What they don’t know, is the majority of children in institutions aren’t orphans, but have at least one living parent.

These orphanages are sometimes seen as an appropriate response to perceived ‘orphan crises’. These ‘crises’ can be linked to wars, natural disasters or health pandemics like COVID, HIV/AIDS and Ebola. While many children do lose parents in crises, most of those ending up in institutions are displaced, separated from their families, not orphaned. Nearly all children confined to orphanages have family that could care for them, with support.

How orphanages cause family separation

Professionals in the sector increasingly recognise that institutional care creates a vicious circle. The very existence of orphanages causes children to be separated from their families. In several countries, most children in institutions are left there by parents who lacked the means to care for them.

Poverty

Poverty is in fact a significant underlying reason for children ending up in orphanages. Many parents struggle to provide food, housing, medicine and access to education for their children. They’re led to believe that orphanages will provide them with a better future. Institution managers and staff sometimes actively invite parents living in poverty to place children in their facilities. They promise services, nutrition, shelter, access to education, health care and better chances for the children.

Orphanages cover up social problems

Orphanages, therefore, don’t respond to orphan crises: instead they actively contribute to family separation. Worse, they provide a one-size-fits-all response to deeper societal problems, which are then left unaddressed.

Orphanages perpetuate discrimination

Where mechanisms for protecting children’s rights are weak, institutions are used to isolate specific groups of children, perceived as unfit for life in the community:

- children with disabilities

- those belonging to ethnic minorities

- children born out of wedlock,

- and children living with HIV/AIDS

So orphanages perpetuate a system of structural discrimination.

Orphanages are not the answer

Naturally, a smaller percentage of children are in institutional care because of orphanhood, severe neglect or abuse. While care outside the birth or extended family may be necessary and in the best interest of the child, institutions can never offer an adequate solution for children without parental care. A range of family- and community-based options should be available to provide appropriate support and quality care to children in their communities.

Learn more Why do children end up in orphanages?

Discover the push and pull factors causing untold suffering to millions of children

The post Orphanages are the problem appeared first on Hope and Homes for Children.

]]>