The exhumation of dead babies from a mass grave on the site of an orphanage in Ireland is not the consequence of an isolated tragedy. The evidence is conclusive. Orphanages have proven to be associated with high levels of child mortality around the world for a long time. They still are. And children who otherwise might have lived continue to die in them.

Hope and Homes for Children is doing something about that.

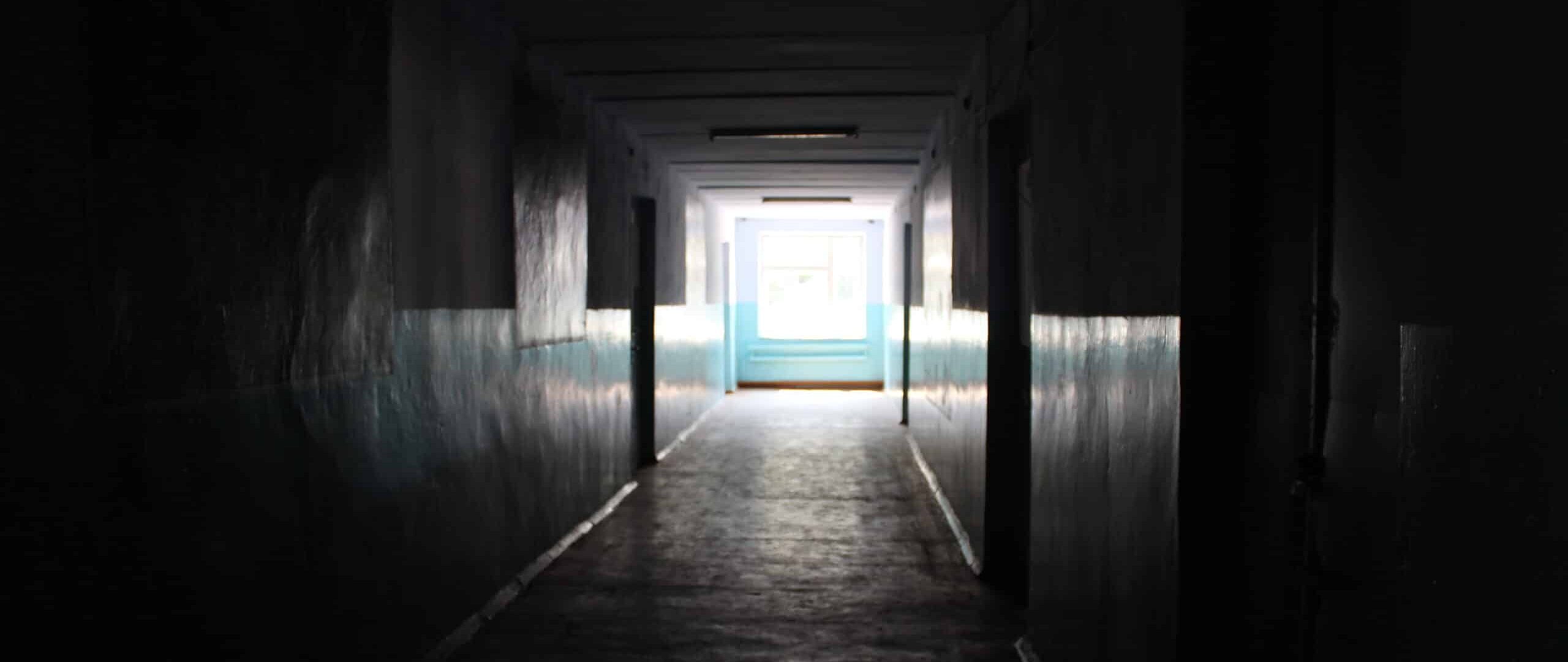

Today, Monday 14th July, investigators will finally be moving diggers in to open up a mass grave on the site of a now closed orphanage, St Mary’s, in County Galway, Ireland.

According to the 2021 Final Report of the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes, approximately 3,200 children were confined in St Mary’s during the 36 years it was in operation. 796 of those children are known to have died during that time – an average of 22 per year. That’s a catastrophic mortality rate of 220 children per 1,000 over the period. To put that in context, the current under five mortality rate of Ireland is 3.8 children per 1,000.

St Mary’s was part of an industrial complex of abuse and neglect. The same 2021 report, which reviewed the experiences of children and young mothers nationally, between 1922 and 1998, estimated that 9,000 children, or 1 in 7 born in those orphanages, died within them. A mortality rate of 143 per 1,000. Even 85 years ago, in 1940, an already high national infant mortality was much less than half that level at approximately 66 per 1,000.

Just as St Mary’s did not exist in isolation of the wider Irish experience, neither does the Irish experience sit in isolation of the wider international experience. The Bucharest Early Intervention Project evidenced that for children under 3, confined in orphanage settings in Romania, Russia and China, they lost one month of physical growth for every three months of confinement. Delays in physical growth like this, as indicated via stunting (low height-for-age) and wasting (low weight-for-height), can significantly increase mortality rates in children, especially infants.

The 2020 Lancet Commission review on Institutionalisation and Deinstitutionalisation robustly documents serious health and developmental harms resulting from institutionalisation, which are well-established causal factors of elevated infant mortality. Indeed, Harvard University’s Centre on the Developing Child has built up a similarly robust evidence base over the years.

Research into the consequences of the process of institutionalisation, which impacts children in all orphanage settings, goes back over more than 120 years to early studies of mortality rates in US orphanages, and the figures are harrowing: virtually all infants admitted into institutional care died, with mortality vastly exceeding typical urban infant rates of that era. Indeed, Dr. Dwight Chapin, analysing institutionalised infants in nine major U.S. cities in the early 20th Century, provided evidence that nearly 100% of children under 2 in orphanages and foundling institutions died.

None of this is news to the survivors of St Mary’s. Mr PJ Haverty, who spent the first six years of his life in confinement there. Mr Haverty, who was recently interviewed by the BBC was clear that he was lucky to survive, and described the home as a prison. Sadly, this is not unusual for orphanage settings. The 2019 UN Global Study on Children Deprived of Liberty (A/74/136), addressing orphanages as places that inherently deprive children of freedom, stated:

“Institutions, by their very nature, are unable to operate without depriving children of their liberty: physical restraints, isolation and solitary confinement occur in some institutions, which are particularly egregious examples of deprivation of liberty, in some instances amounting to torture or ill-treatment.”

I have met children who have been chemically restrained to prevent them telling their story of confinement, and I have seen many more who have been locked in rooms with metal doors, barred windows, in orphanages with barbed wire perimeters. In many countries. When children are isolated from their communities and families like this, hidden away, they become extremely vulnerable to abuse. Recently, one of our local partner organisations was able to rescue 36 blind children from an orphanage in which every single one of them had been sexually abused by the staff. In multiple locations we have identified and alerted authorities to orphanages that have been run as brothels. Sexual violence, torture and trafficking are very real risks to many children confined in orphanages around the world.

Globally, there are 5.4 million children locked away in orphanages. They face de-humanising routines, depersonalised care, neglect and exposure to extreme protection risks. As a consequence, children who would otherwise have lived are dying. Right now. And in this regard, the experience of my own colleague, Otto, articulates the deeply moving impact of that in his own life, in an article run by The Times.

There are no places for orphanages in the 21st Century. Anywhere.

And it doesn’t have to be this way, because here’s the thing, the vast majority of children confined within them are not orphans. More than 80% of them have one or more biological parents still alive, while many more have extended family. That means, with the right support, we can get them #BackToFamily. For those children for whom this is not possible, we should not be punishing them with confinement, but developing alternative forms of family care, including supporting kinship care options with relatives, and where appropriate, properly supported foster care.

Here’s the really good news, all the evidence that Hope and Homes for Children has collected from its frontline experiences of transitioning children out of orphanages and into family care, demonstrates very significant improvements in development, cognition and well-being, to the extent that children catch up to where they should be. And get this, because there is so much money locked up in huge orphanage economies around the world, much of what is needed to deliver reform already exists in the system, and can be unlocked. When it is, the dividends are immense, including improved educational outcomes, improved earning potential, improved health outcomes, and above all, hope for those who need it most.

Hope and Homes for Children has proven all this can be delivered at scale. When we first began our work in Romania, more than 100,000 children were confined within its system of institutions. We have helped to reduce that to less than 1,700. In Moldova we have helped to reduce the number of children confined from 13,000 to less than 800. In Rwanda we have less than 180 children to get #BackToFamily, and in Bulgaria we have just 2 institutions left to close. We are contributing to the foundations for similar success in Kenya, Uganda, South Africa, India and Nepal, and most recently, Madagascar. Our local partners and local teams, all of whom are nationals of their own countries, are developing home-grown, locally appropriate and sustainable solutions that are progressing national reform in ways that are saving as well as transforming children’s lives for the better. And we are seeing increasing levels of international interest and support. Despite the troubles that the world faces, we still have hope. We always have hope.

If you can, please share this post, and support the work of Hope and Homes for Children. You will not only be helping to prevent the deaths, abuse and neglect of children confined in orphanages, but will be offering them a future they might otherwise never have enjoyed.

Mark Waddington CBE

Chief Executive, Hope and Homes for Children